The Hardest Books I’ve Ever Written

How two of the books that scared me the most became my favorites

Whenever someone asks me what my favorite book I’ve written is, I always smile to myself not because it isn’t a valid question but because it isn’t the most revealing question. That would be: what was the hardest book to write and why?

While I remember the books that flowed from my fingertips very fondly (yes, I’m talking about you The Last Garden in England and A Traitor in Whitehall, you wonderfully easy-to-write dreams of books), I’m proudest of the ones that made me sweat, worry, and almost give up. Those books are the ones that left scars but also helped me grow as an author.

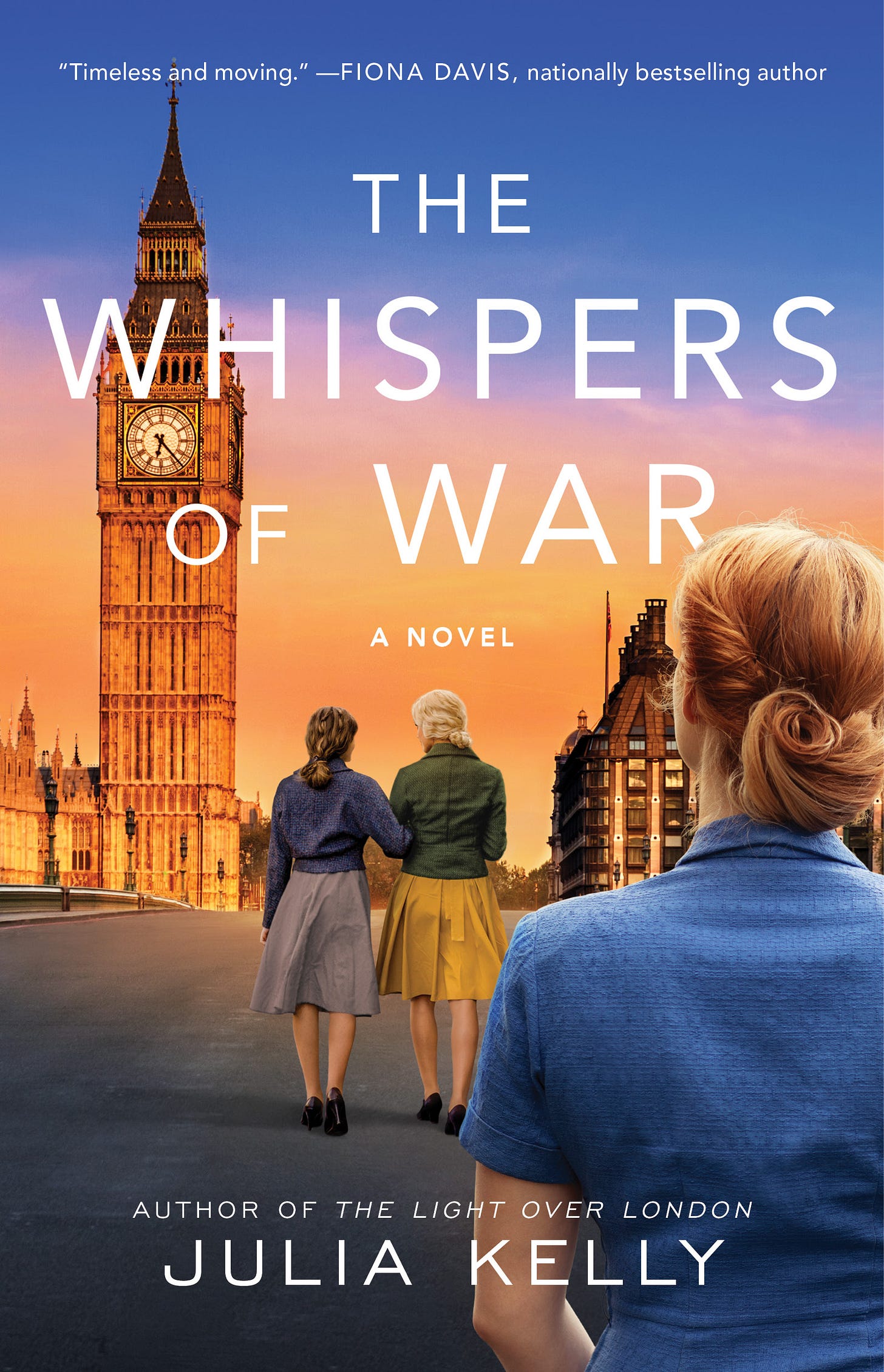

The Whispers of War

There is a reason that people talk about a novelist’s second novel with respectfully fearful reverence. Sophomore books—like second albums for bands—are notoriously difficult for several reasons, but the two that I think are the most profound are time and pressure. After having all the time in the world to write their first book, a novelist is usually writing their second under the pressure of a contractually agreed deadline. Not only do they have expectations for themselves and their work now, their editor and readers do as well.

I will admit, I walked into The Whispers of War with more than a bit of arrogance about me. It was, after all, not my second book but my ninth. However, it was my second historical novel after The Light Over London, which had been a dream to write.

I should have known better.

The irony is that, looking back at it, the plot of The Whispers of War didn’t change that much from pitch to publication. The book is about three women, Marie, Nora, and Hazel, whose friendship is tested when German-born Marie is forced to register as an enemy alien at the start of World War 2. With the memories of Britain’s internment of German citizens during World War 1 far too fresh in her family’s mind, she’s desperate to avoid a similar fate. However, when her association with a fellow German national puts her under suspicion, she and her friends must decide what is more important to them: their loyalty to their country or Marie’s freedom?

If The Whispers of War basically covers the same ground that I expected it to when I first started writing it, why did I struggle so much with it?

Well, it turns out that when you set out to write a three-POV book but you’re not entirely certain how those different perspectives should be woven together, you’re going to run yourself into some trouble.

The book as it was published follows Marie first. Then the story picks up in Nora’s POV for part two and Hazel in part three. However, that’s not how I originally wrote it. At first, I had all three POVs weaving back and forth, but even as I was writing it I knew that something wasn’t working. The book had no flow to it, and although I finished that draft and handed it in to my editor, I knew that I was in for a long slog of a developmental edit.

I was not wrong.

I believe that I ripped that book apart and reordered it three times before it finally gelled into the book the you can read today. The first thing I did was take all of the interwoven stories and lump them together into their own parts. Then I played around with whose POV should go first. Then, when I thought I’d finally gotten it, my editor asked, “This is good, but do you want to make it great?”

Of course I did, but not without letting out a silent scream of despair because it was the book that just would. not. die.

But you know what? I’m glad I listened to my editor because I am proud of that book—so incredibly proud of it—and every time a reader reaches out to me and tells me that they’ve enjoyed reading it I remember everything that went into writing it.

The Lost English Girl

Long-time readers of my newsletters will know a bit about The Lost English Girl. It’s the story of a young mother, estranged from her husband and living at home with her parents in 1939 Liverpool, who has to make the impossible decision to send her child away in the evacuations that happened at the beginning of World War 2.

The opening of the book is inspired by a family legend about a young Catholic girl (my relative) and a young Jewish man who were married and separated on the same day in order to legitimize their unborn child. It was a jumping off story for the book that is subsequently completely fictionalized and follows three POV characters—the husband, wife, and their daughter—throughout the war.

I believe that the reasons that The Lost English Girl was difficult to write were two-fold. Firstly, the subject matter, and therefore the research, was undoubtedly heavy. I read a lot of accounts of Operation Pied Piper, or the decision to evacuate millions of vulnerable people including children from urban areas in Britain to the countryside at the start of the war. Many of these children were uprooted from their families and sent to live with foster families for years. A child who was five at the start of the war would have been eleven at its end. A twelve-year-old would have been eighteen and eligible to fight. The difficulty of that fact alone on children and parents weight on me while I wrote this book, although I hope readers will find hope in it as the story unfolds.

The second reason that I think The Lost English Girl was a tough go was because of my changing life circumstances. I quit my day job in June 2021, and I started writing The Lost English Girl July 15, 2021. It was the first book I wrote as a full-time author, and I didn’t anticipate how much leaving my day job would upend my writing. It makes sense now. I essentially upended all of the systems that I’d had in place to make sure I got words on the page. Instead of 90 minutes every night and some extended time on weekends, I had 8+ hours to write. The annoying irony of full-time writing is that open-ended time can actually make you less efficient than you were when you had less time because there is far less urgency.

Over the course of the first draft of The Lost English Girl I will confess that I wandered, quite literally, all over the place.1 As with The Whispers of War, I knew that something was wrong because writing the book was becoming a slog. However, I couldn’t put my finger on it so I soldiered on bit by bit and handed a bloated manuscript in to my editor and subsequently collapsed like a Victorian lady on a fainting couch for three weeks over Christmas.

That same editor came back with notes in the new year confirming what I already knew: the ending wasn’t working. Luckily, the time away from the book had left me with enough space to figure out what I needed to do. I cut the entire third act and rewrote it, picking the action up right after V-E Day in 1945.

It worked. The words started flowing again and, after some brutal editing, I managed to whittle down the book down to the essence of the story I was trying to tell.

That and the very emotional story behind the story is the reason that The Lost English Girl is one of my favorite books I’ve ever written.

There was a time when the third part of the book picked up in 1961. There is no 1961 section in the final novel.